What’s life without a little adventure? Tim Shuff shares a story of extreme backcountry fishing when he and four friends gathered to take on the wilds of British Columbia. The anglers traveled to Haida Gwaii, known as “Canada’s Galapagos” for its pristine landscape, profusion of wildlife and fantastic fishing opportunities. Over a week they tried for tyee, monster halibut and more as they contended with storms, swells and the wettest summer in 80 years.

Extreme Backcountry Fishing in Haida Gwaii

“It’s the last day to go big or go home,” says Jeff as he hands me his burliest G.Loomis halibut rod and loads a 16/0 circle hook with a two-pound dolly varden that I would have considered a good catch back east. He tells me to paddle out and drop the hook to the bottom in 30 fathoms and watch for the rod tip to dip.

“When you see that, put the reel in free spool. Count to ten nice and slow and let the halibut eat the bait, flip the reel in gear, loosen the drag, and hang on. Whatever you do, don’t lift a halibut out of the water. Just call for help.”

Hours later I’m turning green in a washing machine. On the open Pacific in a 12-foot swell, there is really no such thing as feeling bottom. I can only guess. Every eight seconds the sea bucks and I feel the yaw of my massive ‘but bait.

All the other kayaks have scuttled inland and disappeared in a fog. But it’s my last chance to catch a big one and I won’t go in. I take my eyes off the rod and look at the horizon, warily at the ring of sea foam around the black wave-blasted rocks. Then I check the depth finder and edge out towards Siberia, feeling my way into 300 feet of water.

My beautiful trout hangs down there in the dark, bouncing in front of the nose of something 100 times its size. I feel the unmistakable tug-tug of a strike and begin my count for the monster to swallow—one, two, three, four, five….

Blame the Internet

I’m trying to put together a sweet world-class yak fishing trip up here…It would be a one week camping trip on the west coast of the Charlottes when the weather is usually best and the fishing rocks. We would take a mother ship from port and tow a Zodiac and four yaks to an area I’ve scoped…Do a bit of fishing, prawning (14 inchers), crabbing (endless #’s of crabs) and maybe some mushroom picking (golden chanterelles)…Mostly fishing I’m guessing…lol… Target species here at that time are bigger chinook salmon, coho, halibut, ling and rockfish…Also some great time with fellow anglers…If you’re interested let me know, K? Luv Life, Live Now, Fish Hard – Jeff

Thirty-year-old Jeff Goudreau lives in Port Clements, a no-stoplight logging town deep in the cloudy heart of British Columbia’s Haida Gwaii that gets twice as much rain as Seattle. Jeff toils 60 hours a week running logistics at a logging company desk, and when things are going smoothly, he cruises the fishing forums, putting up winter cabin-fever postings and scheming about trips like this one.

Four of us took the bait from four corners of North America. Me, a magazine editor from Toronto. Wali, a high school science teacher who divides his time between Jacksonville and Portland. Jesse, a laid back Californian fresh in from Istanbul, whose career is on hold while he does more important things like sailing the Mediterranean and fishing Haida Gwaii. And Lucian, an Ocean Kayak pro from Michigan.

I recognize them immediately in the Vancouver airport, casually dressed guys with tans and fishing shirts and rod cases strike up an instant conversation. We board the small plane elbow to elbow with grey-haired ladies going to see the Haida totem poles and anglers destined for world class luxury lodges. We’re headed to a place so remotely wild and biologically productive that it’s known as “Canada’s Galapagos.”

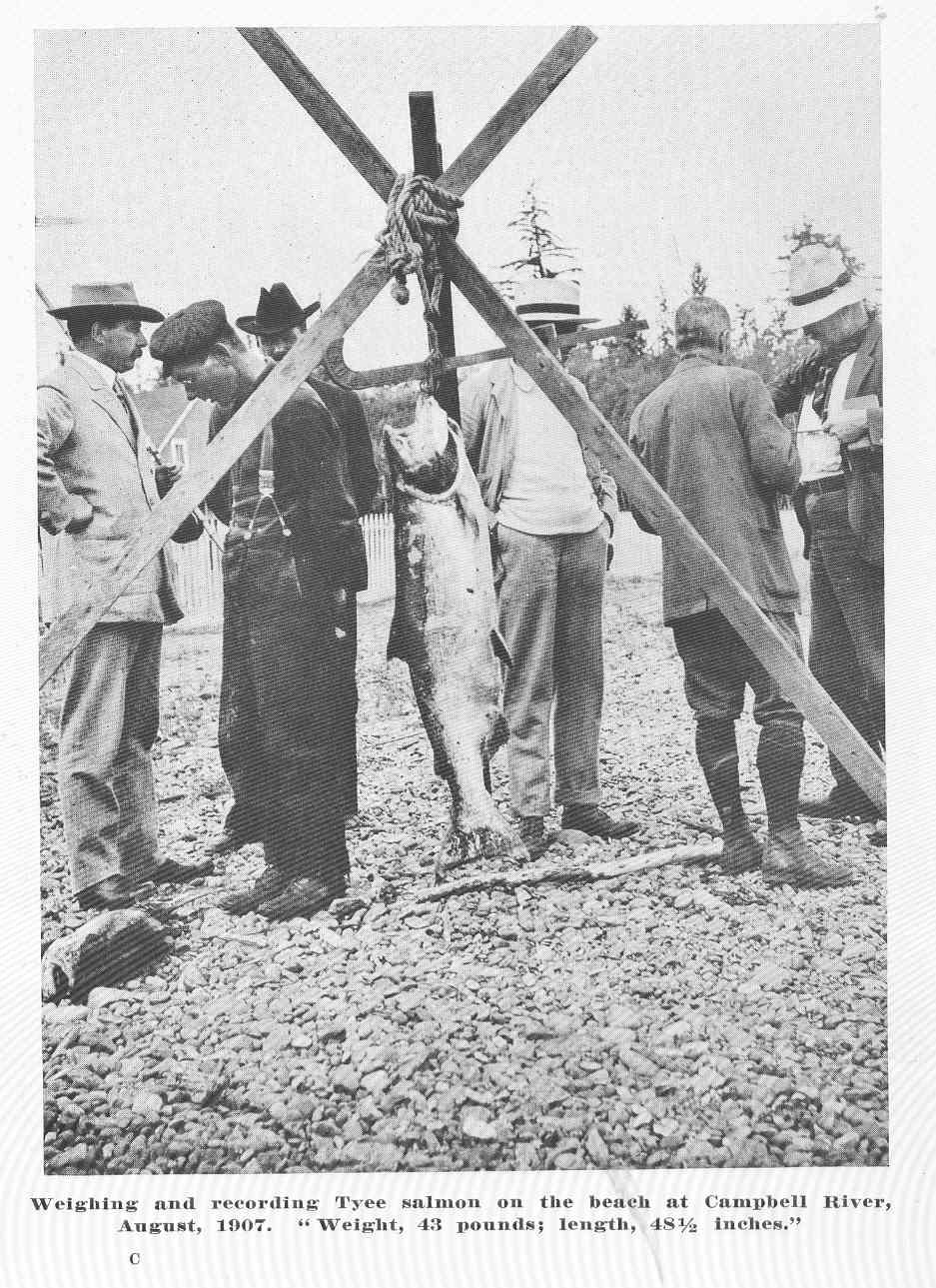

All local fishermen dream of catching a tyee. Tyee, meaning “the chief,” is what the coastal tribes called a 30-pound-plus chinook salmon. When our plane lands in Sandspit, outbound travelers stand in line to check box after box of frozen packed salmon and halibut, haggling with the agents about weight restrictions and shelling out for over-limits. One of these might be the season-record 67-pounder that we’d read about, one of eight 40-pound-plus chinook reported just last week in the very place we’re headed.

Two hours later, we toast a sunny afternoon on the deck of our chartered 50-foot sailboat, surrounded by kayaks and coolers full of bait on ice—two hundred dollars’ worth of herring, anchovies, octopus, trout and squid.

“Tomorrow we pound fish,” says Jeff, raising a can of Bud. We cruise out of Queen Charlotte City towards the gathering clouds on the west coast of Moresby Island. We’ve shipped out a day early to beat a coming storm. The forecast says that tomorrow could be our only good day of fishing.

Sometime after midnight we arrive in darkness trailing a shimmering phosphorescent wake, as if the world has turned upside down and we are sailing through a starry sky. At the end of a day that started with driving to the airport in rush hour traffic, we drop anchor on the very western edge of what the natives called “the islands at the boundary of the world” and are rocked asleep by the tide.

Joining the Tyee Club

“I don’t need to eat. I’m running on coffee and adrenaline.” Jeff’s rallying cry is the first thing we hear at 5:30 a.m., which might as well have been, “I love the smell of herring in the morning.”

As a guide, Jeff is eminently concerned about safety on the water, but his attentiveness doesn’t extend to luxuries like an eight-hour sleep and a hot breakfast. Later, after the weather craps out, he tells us about the time he was a freshman fishing guide at a second-rate lodge on a “tiny lake with no fish in it” in northern Canada. One of his clients dropped dead of a heart attack. “It was my first year and I was keen. It was all about production. The poor guy was sweating and I was working him hard.” You can’t quite say that Jeff’s zeal killed the man, but it’s a good reminder not to underestimate the passion that brought us all to this far-flung place.

We unload our camping gear onto a small island and bust out the tackle and start tying leaders and piecing together high-end travel rods. Stacks of Plano boxes full of hooks spread out on the moss alongside Rubbermaid totes packed with of heavyweight jigs and plastics. It’s the same routine no matter where you come from—only Alaska-cold; everyone’s on autopilot rigging boats and pulling on the Gore-Tex and neoprene.

The water’s glass-calm and gently agitating from some old, far-off blowup. The sun burns through a high haze. Jigging for groundfish in an exposed kelp bed with an 8-ounce bullet head, it’s laughably easy. Every time I drop my grub to the bottom, a bite. We haul in a rainbow of rockfish. Then, just like that, I fight and boat a mini-monster, a toothy green 41-inch lingcod. Minutes later, Lucian holds up its twin.

Meanwhile, Jesse’s smiling ear to ear, double-fisting a couple of poultry-sized yelloweyes the color of aquarium goldfish—one of which followed a smaller one onto the hook, so that Jesse pulled in two at once. Everywhere I look, someone’s lip-gripping, releasing, threading a stringer, and Wali’s snapping pics with a waterproof point-and-shoot. Jeff’s beaming around us in the Zodiac like a winning soccer coach because his winter cabin fever has finally broken and his one-day-old fishing team is cleaning up.

Grilled rockfish and cod are on the menu for dinner. We clean a bucketload of fillets on the beach. Then it’s time for an evening session.

There’s a deep channel off camp that’s a spawning-salmon highway, one of the many features that made Jeff choose this particular secret spot amongst this mass of islands. Lucian works the edge of the underwater canyon with quiet Yugoslavian-American determination, applying all his Great Lakes salmon-fishing know-how. It’s the same drill he uses back home on Lake Michigan. He cranks his downrigger to 50 feet and trolls a spoon back and forth with military precision until I hear him yelling my name. I find him struggling with a lap-load of silver muscle, grinning through the black mesh of a giant net. He’s got a tyee for sure, what turns out to be a 37-pounder.

The strict and gentlemanly definition of a tyee—according to the 85-year-old Tyee Club of British Columbia—is a 30-pound or larger chinook caught on an artificial lure from a rowed boat on 20-pound-test or lighter. In the famous Tyee Pool near Campbell River, B.C., where fisherman J.A. Wiborn started the Tyee Club in 1924, anglers aren’t allowed motors. Most use old-school rowboats.

Fishing from a Trident 15 with 15-pound braid and a 20-pound fluorocarbon leader, Lucian’s just redefined the rules. “Yeah baby,” Jeff motors in and gives Lucian a high five. “Now that’s what I call a true tyee. A tyee caught from a kayak!”

Roughing It in the Bush

After that first good day, the storm blasted away a week’s worth of fishing. This year’s La Niña weather pattern has trashed Jeff’s carefully plotted 30 years of seasonal norms. He says the island old timers have been calling it the wettest summer in 80 years.

Our camp is no fancy pants fishing lodge either. We see the lodge boats and hear them on our VHF radios, ranging far and wide to find biting fish. They have five-star chefs, helicopters, hot tubs and sexy massage therapists. We’re hunkered in tents on a ragged little island, spending our vacation with four other smelly guys in drysuits. And now the fishing’s gone bust.

A bonfire rages, bellowed by the 50-knot gale which blasts sparks up into the jet-roaring treetops, an empty bottle raised, hearing a victorious whoop.

Jeff’s prawn trap got blown into the abyss. The crabs aren’t taking the bait. Nothing we can paddle to inshore is biting. After flying all these thousands of miles, we’re just pissing our time away in the rain. And because we didn’t anticipate needing enough libations for weather like this, we are running out of booze, ironically sitting on coolers full of ice that are loaded with nothing but slimy, thawing bait.

Not that we need more fish. We feast on Jeff’s special venison shanks marinated in white wine and lime leaves, and our 60-odd pounds of salmon fillets, cod and snapper cooked 10 different ways. One day I fall asleep mid-afternoon with a belly full of fish and awake in darkness to the sound of voices and a choking smoke blowing up a gulley from the beach. I zip open my tent and stand shaking in the horizontal rain. A bonfire rages, bellowed by the 50-knot gale which blasts sparks up into the jet-roaring treetops. I watch the zombie silhouettes illuminated by dancing firelight, see an empty bottle raised, hear a victorious whoop. An otherworldly howl of laughter crosses my ears before it is ripped away by the wind. In the early hours, Jeff stumbles up to the tents and slurs across to me with eternal optimism, “Wake me up in the morning, ‘k? Promise to wake me up. We got a plan. I’m gonna hook you guys up.”

The Final Tally

On the one fishable day after the storm dies off, Jeff sets me up with his halibut rig. One last hope of reeling in a lunker ending to this story keeps me trying after the others have gone in. Bobbing in waves as big as my house, munching on cold fried cod and salmon cakes, eight hours pass with nothing but one lousy lingcod and a dozen phantom strikes. Every monster I wrestle turns out to be just another lash of La Niña’s whip toying with my imagination, stirring up the waters and making the fish unseasonably edgy.

I close my eyes and can still feel the rise and fall of the swell, see the ghostly mist hanging over the islands and a humpback whale breaching into the sky before crashing back to sea with a boom.

On the return to port, everyone’s in high spirits but Jeff, who harbored our hundred-pound halibut dreams. Lucian’s tyee was the trip trophy; the halibut had us skunked.

Back at the airport, we fall in with the lodge crowd and their cartloads of fish boxes. Their frozen haul is one version of the fishing story, but not what our trip was about.

I close my eyes and can still feel the rise and fall of the swell on the rim of the Pacific, see the ghostly mist hanging over the islands and, half a mile offshore, a humpback whale breaching into the sky before crashing back to sea with a boom. We are the only ones on the plane with such a bounty of wild memories.

We are the only ones who have spent the week camped out, fishing without motors. We fished harder. We saw more. We fished Haida Gwaii in kayaks.

Backcountry fishing in Haida Gwaii is an unforgettable experience. | Feature photo: Tim Shuff